Carbon-negative cement can be made with a mineral that helps catch CO2

An abundant mineral called olivine can help make carbon-negative cement. This process could help tackle cement’s large carbon footprint – the material contributes about 8 per cent of global CO2 emissions.

Olivine is one of the main components of Earth’s mantle and reserves sit on every continent. “It’s one of the few minerals that is available at the gigatonne scale,” says Sam Draper at Seratech, a UK-based company that has patented a process to turn olivine into cement.

Dozens of start-ups like Seratech are developing low-carbon methods to produce cement, such as supplementing with steel by-products or recycling the CO2 released in cement production. Most emissions occur when heating limestone to produce clinker, a binder in cement, along with burning fossil fuels to generate the heat.

Draper and his colleagues looked to the more abundant olivine to find a replacement for some of the usual clinker. Olivine contains silica, which makes cement stronger and more durable. Magnesium sulphate can also be extracted from it, and this salt reacts with CO2 to form minerals that sequester the gas.

The researchers extracted these compounds by dissolving powdered olivine in sulphuric acid. After separating the silica and magnesium sulphate, they bubbled CO2 through the magnesium slurry to form a mineral called nesquehonite. To scale up the process, Draper says a cement plant would use CO2 captured from an emissions source or from the air, rendering the entire process carbon negative. The leftover nesquehonite could be recycled into new construction materials like bricks.

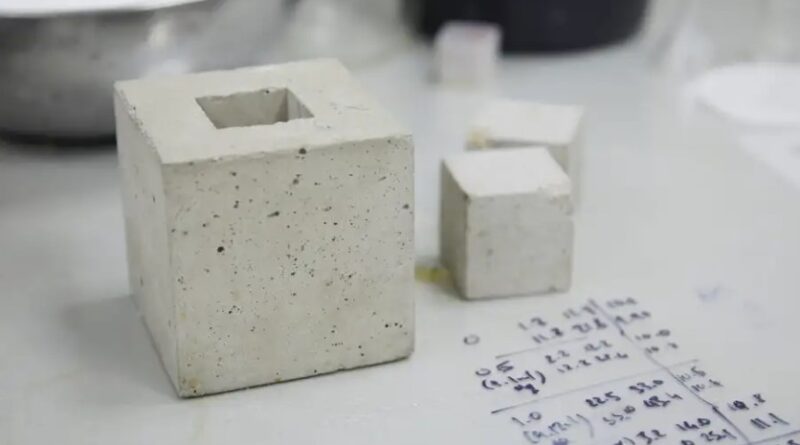

Replacing 35 per cent of the regular cement in a concrete mix with silica from this process would produce a carbon-neutral cement, the researchers estimated, while subbing 40 per cent or more would make it carbon negative. Draper says current building standards allow this type of material to replace up to 55 per cent of cement, although he says they haven’t yet made enough of it for robust testing.

The process utilises well-known reactions, says Rafael Santos at the University of Guelph in Canada, but offers a novel and “reasonable” way to combine them. However, some of the chemicals involved may prove tricky to recycle, he says.